I wanted to spend some time this morning talking about Anita Sarkeesian’s latest Tropes vs. Women video, “Ms. Male Character.” If you’ve listened to the podcast since I joined, you might know I’m not always Sarkeesian’s biggest fan. I support the work she does, but not always the way it’s done, though I’ll grant it’s work that desperately needs doing (hi, welcome to our website!). Her latest video, however, strikes true on all fronts, so far as I’m concerned; it’s a clear, well-researched proposition, and a thorough look at one of the biggest problems for women in gaming — in my opinion, at least.

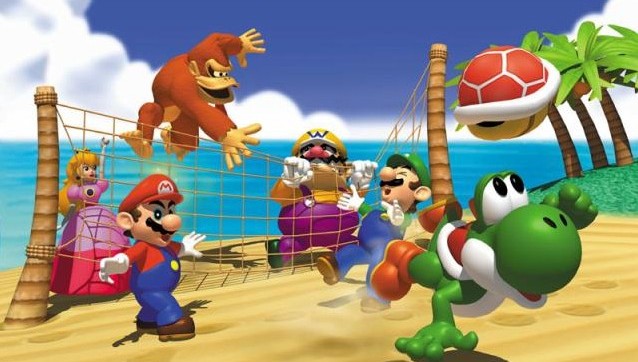

In this latest video, Sarkeesian explores the put-a-bow-on-it approach to shallow female characters: “women” (or female creatures and representations) identified as female through a few daubs of makeup and “girly” attitudes, and through a number of game examples, identifies the pervasive and negative qualities of this approach to character design. One of my favorite examples presented here is the Koopalings. The male Koopalings each have a distinct personality, while Wendy O. Koopa’s dominant trait is simply that she is the girl. While all the Koopalings fall into some trope trap — Lemmy is the crazy one, Roy the brawny one — Wendy is only the girl. That’s it.

Sarkeesian’s examination of Wendy O. Koopa is a springboard for exploration of the Smurfette principle, the notion, outlined by Katha Pollitt, that “boys are the norm, girls the variation; boys are central, girls peripheral; boys are individuals, girls types. Boys define the group, its story and its code of values. Girls exist only in relation to boys.”

Sarkeesian’s examination of Wendy O. Koopa is a springboard for exploration of the Smurfette principle, the notion, outlined by Katha Pollitt, that “boys are the norm, girls the variation; boys are central, girls peripheral; boys are individuals, girls types. Boys define the group, its story and its code of values. Girls exist only in relation to boys.”

In this video, Sarkeesian looks not only at the put-a-bow-on-it approach to feminizing characters, but also the Smurfette principle, as well as the idea that the token woman is often presented as vain, shallow, and quick to fly into blind rages — characteristics that dominate in iconic female game presentations. Examples include not only Wendy O. Koopa, but Ms. Pac-Man, and Wonder Pink from The Wonderful 101.

Another great example in the video of women-outside-the-norm can be found in Angry Birds. As Sarkeesian points out, the introduction of female-coded birds in later versions of the game make clear that, outside of those girl-type birds, the Angry Birds universe is male-dominated. Male birds are the default. Females are added when needed, as seasoning.

Sarkeesian also talks about so-called BroShep vs. so-called FemShep in the marketing and presentation of Mass Effect, though she only uses the latter term, the one more common in discourse on the game. BroShep, she says, is the default, and in most of the marketing, that’s true. While FemShep is beloved by those who played her… she’s still the lesser Shepherd.

In this video, the tropes at hand are presented clearly and are backed with great examples, and balanced with examples of games, largely indie titles, that do a much better job presenting women without defaulting to bows and high heels and a love of fashion.

For the most part, reaction has been more positive to this video than to some of her others (I see I’m not alone), though of course, Sarkeesian has her vehement detractors, many of whom started slinging slurs and rage before there’d even been time to watch the video in its entirety. But perhaps more interesting, at least to me, was the number of people I found commenting on forums and on posts, engaging in the discussion by making assumptions. A commenter on Kotaku was quick to point out that Minnie Mouse is an example of a woman who exists only in relation to her male counterpart, and is simply a bow-bedecked version of the male, a point that was, in fact, made in the video.

Others pulled out the usual saws. “But all tropes are bad; it just means lazy storytelling!” While that’s sometimes true, every trope is not a trope that singles out an entire group for lesser presentation, which is a significant portion of the “point” of Sarkeesian’s projects: these particular tropes identify damaging portrayals and treatment of women.

Still others just made stabs in the dark based on a few grabbed facts or ideas about the video. For example, in the thread on the NeoGAF forum, the original post linking the video included the list of referenced games. One poster, who obviously didn’t watch the video, immediately jumped on Sarkeesian’s use of Thomas Was Alone, saying, “I don’t really understand this complaint for some of those games. Thomas Was Alones female character was completely distinct personality wise. So the lead was male, is the only solution in her view to make every lead female?”

In reality, Sarkeesian used that game as a positive example, praising the game for the presentation of Claire, a featureless super-powered block with a female name, without any stereotypical and shallow gender signifiers. There was no mention of a need for Claire to be the lead, or a statement on lead versus non-lead at all — but these are the kinds of assumptions that dominate discussions of feminist explorations of games. When we complain, it’s because it’s assumed we want something we don’t want, so let me take this opportunity to jump on my soapbox and make something clear:

While I do not speak for all female gamers, here’s what I want, and what I know many other women want: we want female characters who wear normal clothing, who are not presented for the sole purpose of titillating male audiences, who have personalities and abilities that reflect complex dynamics — or at least as complex as those presented by male characters in the same game. (It’s cool to be the lead, too; that’d be nice if it happened more often, because we are hell of tired of being saved all the time.)

Here’s (some of; there’s more) what Sarkeesian takes issue with (and I do as well): slapping a heart or a bow on a figure or shape and saying, look! It’s a girl! Now we appeal to women — without doing any further work. No one should pat themselves on the back over Toadette, you know? That’s not advancing equality; that’s tossing in a Smurfette.

The posts identified here are just examples. There’s more, like the group outlined here, who believe Sarkeesian has purposely sought to be harassed, and these folks, who seemingly do not understand Internet and how magical Internet works, as they feel that, by disabling YouTube comments, Sarkeesian has turned off the Internet and disallowed any argument against her work. A petition (on the Internet) is clearly the only solution.

I guess those guys don’t read gaming sites.

2 thoughts on “Put a Bow on It: The Latest from Anita Sarkeesian”

Good article.

I felt that some of Anita’s early work was a bit off the mark, but her video game series has been spot on.

I’m curious to know what criticisms you have of her work?

I have to admit that I like this segment of the video games series more than I have liked the previous ones. I have appreciated her work as a step in the right direction and I am very glad to see that the momentum continues. But the important thing to remember is that Sarkeesian is not a games scholar. She only bills herself as a pop culture critic, I believe. (Important for me that is)