This week, over 3,000 academics gathered in sunny, warm Tampa, Florida to talk about writing and language and consume every bit of coffee the unprepared Mariott hotel had to offer. It was the 66th meeting of the Conference of College Composition and Communication (affectionately known as Cs), a hub for scholars interested in language, culture, and writing.

For three days scholars rushed between buildings, anxious to get to panels before chairs were taken or the few vestiges of free food disappeared. In the center of it all was the Action Hub: a giant conference room where people could gather, take in poster presentations, and win a Sparklepony.

As background for the uninitiated, Cs is immense. When I arrived (this was my first year) I asked for a program and was promptly handed a book. A thick book. Where many other conferences have set blocks of time devoted to food or breaks, Cs offers no such relief. There are five million things to see, and only two million moments to do so. For someone new to the conference, it can be overwhelming and intimidating.

Six years ago, assistant professor Wendi Sierra (then a graduate student) helped to create a WoW-inspired game called Cs the Day. Players (new and old) get a booklet with “quests” that include challenges like buying a newcomer a drink, skipping a party to go to a special interest group (or suffering through a hangover to get to an 8am panel after a party), or to network with fellow scholars and find out what they are working on. Players can try to complete quests on their own, or join up with others to form a guild…and the reward for success is the Sparklepony.

Two years ago, Cs the Day was highlighted by the Chronicle of Higher Education…and then quickly lambasted by a writer for Gawker. According to writer Adam Weinstein, the game was mockworthy, with the prizes not worth the effort needed to achieve them. Weinstein’s critique of the “pun-based scavenger hunt” hinged on the idea that navigating conferences was simple and second nature and not something that needed additional instruction, and if that was true he’d be right in picking apart the game. Gamification (the use of game mechanics to help people engage with tasks that are normally not game-related) can be problematic. Successful use requires game designers to be familiar both with the activities they are trying to promote AND game design and mechanics. Sierra–a professor of games, rhetoric, and digital media–has that expertise, and an intimate, empathetic knowledge of how intimidating a conference like Cs can be for budding scholars. Weinstein may be right that, with time, navigating and networking at the giant conference becomes second nature, but for first-time graduate students, new professors, or even people who need some help finding an opening for conversation, Cs the Day offers a low-risk, tongue-in-cheek way to find your feet and make the most of your time. And, thankfully, the game is gaining traction with the conference–even getting a shoutout in Chair Dr. Adam Banks’s inspiring keynote address!

Cs the Day isn’t perfect, but it is optional, light-hearted, low-risk, and customizable–which is exactly what you’d want from a game. Even better, games are becoming more and more of an interest at the conference (which for us games scholars is a huge thrill, and hopefully means we’ll have more freedom at more universities as we use game skills and mechanics in our classrooms). The Games Special Interest Group (SIG) which met on Friday night was huge, and had a wonderfully split audience, with male and female participants being almost 50/50.

However, if Weinstein is looking for a new target, there was still a holdout lingering among the vendors. Mixed in with the publishers and textbooks was the Toolwire booth–a self-billed “experiential learning community.” And, at first, the booth looks promising. Toolwire, in collaboration with the University of Phoenix, has created a game called Live!News which is meant to simulate writing tasks for first year composition students in short, twenty minute sessions. The game sessions are web-based and cheap (only $3 per unit) so they are accessible and affordable.

Unfortunately, that’s about where the good points stop. Live!News is the epitome of “edutainment”–where game designers construct false, flimsy facades to try and entice players into practicing the skills they need to learn. The lessons themselves aren’t necessarily bad (the citation app, at least, showed promise), but the vast majority of the apps over-simplified the complexity of language, relied on over-the-top and unrealistic scenarios (you are supposed to be the head honcho of a daily news team, but for some reason you’re stuck fixing all your interns’ writing mistakes), and fell far short of the level most professors would want their students to be at.

To be fair, Toolwire’s creation isn’t meant to replace classroom instruction, so it’s not a fatal flaw that they aren’t the most challenging of activities. At its best, some of the apps imitate the Mavis Beacon – Typing Tutor games (which I kind of loved….), where they might be silly, but they are effective at teaching things like where the punctuation goes in APA style. But its not a “game.” At least with the Mavis Beacon games, typing is a skill that can be valuable in a lot of personal and industry applications, as well as in the classroom. Unless our first-year composition students are looking to spend a lifetime in academia or research (which only some of them are), Toolwire’s goals are ultimately classroom-bound. There is no look at language, subjectivity, or multiplicity of meaning. It is a “game” that teaches the only things that can be easily programmed–grammar and sentence structure.

Live!News also fails in one other important element….student input doesn’t really matter. Before starting the game, students do a “pre-test” to see what they need to work on, but that test does nothing to effect the content of the game. If they ace all the basic skills, there are no more challenging ones for them to tackle. There is completion, but no sense of growth or progress (which I talked about earlier this week with Serious Games).

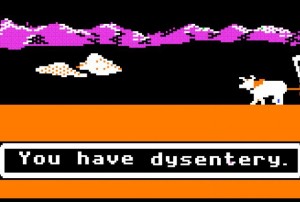

Here is the tricky thing about educational games–to be effective, they have to be teaching something the player actually wants to learn, and they have to be good for more than just a single purpose. Oregon Trail has a fond place in many a 90s-kid’s heart because it really was a game. The threats of dysentery and cholera were real, if only for that precious hour of computer lab time, and there was a thrill in putting all of your friends into your wagon party (and, all-too-often, watching them die off one at a time. Oops). Mavis Beacon pushed the limits of edutainment, but offered a skill that was useful in a lot of contexts,while also avoiding insulting its players by being overly simplistic. If you took a test to see your typing level, the lessons changed accordingly. So too with Duolingo, a site where you can earn badges, gain levels, and compete with friends on a leaderboard as you work your way through learning a language. Or HabitRPG, which is maybe the closest parallel to Cs the Day. HabitRPG is basically a glorified to-do list. You gain experience by completing your daily tasks and you have an avatar that you can equip with weapons and armor for “fighting” bosses (you do damage by keeping up with your lists). You can form parties with friends and add special challenges to your tasks. It is obvious gamification…but it works for the same reason that Cs the Day works–it is fully customizable and optional. Players engaging with these games are doing so because they want to, not because they were assigned to in a classroom setting. The difficulty is adjustable, the incentives are silly but still show markers of success and growth, and loss is frustrating but not devastating.

Here is the tricky thing about educational games–to be effective, they have to be teaching something the player actually wants to learn, and they have to be good for more than just a single purpose. Oregon Trail has a fond place in many a 90s-kid’s heart because it really was a game. The threats of dysentery and cholera were real, if only for that precious hour of computer lab time, and there was a thrill in putting all of your friends into your wagon party (and, all-too-often, watching them die off one at a time. Oops). Mavis Beacon pushed the limits of edutainment, but offered a skill that was useful in a lot of contexts,while also avoiding insulting its players by being overly simplistic. If you took a test to see your typing level, the lessons changed accordingly. So too with Duolingo, a site where you can earn badges, gain levels, and compete with friends on a leaderboard as you work your way through learning a language. Or HabitRPG, which is maybe the closest parallel to Cs the Day. HabitRPG is basically a glorified to-do list. You gain experience by completing your daily tasks and you have an avatar that you can equip with weapons and armor for “fighting” bosses (you do damage by keeping up with your lists). You can form parties with friends and add special challenges to your tasks. It is obvious gamification…but it works for the same reason that Cs the Day works–it is fully customizable and optional. Players engaging with these games are doing so because they want to, not because they were assigned to in a classroom setting. The difficulty is adjustable, the incentives are silly but still show markers of success and growth, and loss is frustrating but not devastating.

As teachers, parents, older siblings, and scholars, we recognize that games are amazing teaching tools, and we celebrate their inclusion in classrooms. I know I want more games, rather than less. But edutainment is not an acceptable middle ground, and such “games” are the reason games studies is still side-eyed by so many observers. If we want to see students grow and learn through gameplaying, we need more innovators like Sierra and a few less opportunists like Toolwire.

One thought on “When is a Game not a Game: Edutainment, Gamification, and Learning”

I just want to add a quick shout out here to all my collaborators- C’s the Day is a group effort, and there’s no way it would be what it is without the involvement of Emi Bunner, Mary Karcher, Scott Reed, and Sheryl Ruszkiewicz, and the legacy support of Doug Eyman and Jill Morris.