Consider a few of the common components that comprise a narrative: complex characters, conflict, setting, resolution, dialogue, etc. Is dialogue a necessary element? Is a silent protagonist capable of weaving a powerful story that captivates and inspires? I find that videogames are comparable to picture books because they’re both visual mediums that can be visually read or interpreted. In other words, a reader can absolutely draw meaning from elements other than dialogue. In thinking deeper about stories that lack dialogue (whether it’s a wordless picture book or a scriptless game), narratives with little to no dialogue often rely or lean on the characterization of worlds. It’s a unique in that worlds transform into characters with their own stories and personalities. In some ways, the world serves as our reliable or dutiful but silent narrator. The silence that permeates these enigmatic lands is particularly telling.

In Journey, the desert landscape at the beginning of the game is a very different character from the icy mountain at the end of the game. Are they two separate characters or the same character? The desert landscape’s is very inviting with its warm colors and soft sand dunes. Its appearance and the way in which the robed protagonist interacts with it is revealing of its nature and personality. These wordless interactions between the protagonist and the desert are very playful and innocent. The two establish a kind of relationship that feels sacred and loving, and in one beautiful instance, the protagonist gently slides down a colossal sand dune as a golden sun sets in the distance. However, when the player reaches the end of the game, the landscape becomes harsh and dangerous with its icy winds and snowy surroundings. If the ambiguously gendered protagonist stays still for too long, the character will lose its ability to sing and its red robe will freeze.

In Journey, the desert landscape at the beginning of the game is a very different character from the icy mountain at the end of the game. Are they two separate characters or the same character? The desert landscape’s is very inviting with its warm colors and soft sand dunes. Its appearance and the way in which the robed protagonist interacts with it is revealing of its nature and personality. These wordless interactions between the protagonist and the desert are very playful and innocent. The two establish a kind of relationship that feels sacred and loving, and in one beautiful instance, the protagonist gently slides down a colossal sand dune as a golden sun sets in the distance. However, when the player reaches the end of the game, the landscape becomes harsh and dangerous with its icy winds and snowy surroundings. If the ambiguously gendered protagonist stays still for too long, the character will lose its ability to sing and its red robe will freeze.

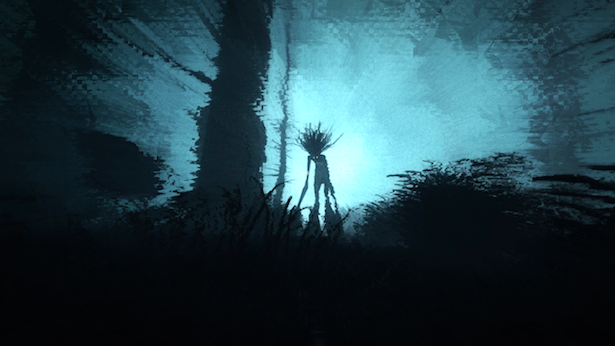

The world in Journey is similar to the somewhat desolate world in Shadow of the Colossus. Both games utilize silence or moments of silence to intensify the player’s experience and to further funnel the player’s focus. Personally, I feel Wander’s world is more isolating because there’s more silence and it’s the kind of silence that’s pressing and a touch suffocating. There’s no accompanying music when I travel from colossus to colossus, but only silence. This type of silence is eerie, isolating, and unsettling. As I guide Wander around on his horse, I realize that, aside from the brutish colossi, only a measly number of lizards and hawks populate the world. In Journey, however, there’s an invisible orchestra wherever I go. It’s hard to feel isolated when there’s music that swells and recedes during the course of my journey. The music acts as a kind of companion, a comforting presence even. The use of silence can firmly set the tone of the overall game.

The ultimate goal of Journey is to reach a floating star atop a faraway mountain but aside from a brief introductory sequence, there’s hardly any comprehensible dialogue or backstory. In revisiting the idea of the world as a narrator, we have to rely on the transitional nature of the landscape and the structures within it for information and meaning. Despite the purposeful vagueness and ambiguity within the game, most can agree that it doesn’t lack an enriched or uniquely crafted narrative. In delving deeper into the idea of characterized structures, there’s something rather archaic about the world in which our soaring protagonist operates in.

Peppered throughout the beige landscape are old structures with hieroglyphic-style paintings on them. These images depict the struggles of figures in white robes. These structures are informative of a culture and language we don’t quite understand. Whether it’s intentional or not, we’re automatically positioned as the outsider. In addition to the smaller structures sprinkled throughout the land there’s also a large, towering structure that resembles a panoptic-style prison. This prison is overflowing with a bunch of flying creatures made of red silk or fabric. In conducting a visual reading of the prison and its prisoners, the world informs us of the unrest and injustice that’s currently occurring. The world, with all of its moments of silent loveliness, has its instances of sheer ugliness as well. For the sake of this exploration, it’s important to question and examine the very silent protagonists we’re sharing our experiences with. Are silent protagonists really silent?

Peppered throughout the beige landscape are old structures with hieroglyphic-style paintings on them. These images depict the struggles of figures in white robes. These structures are informative of a culture and language we don’t quite understand. Whether it’s intentional or not, we’re automatically positioned as the outsider. In addition to the smaller structures sprinkled throughout the land there’s also a large, towering structure that resembles a panoptic-style prison. This prison is overflowing with a bunch of flying creatures made of red silk or fabric. In conducting a visual reading of the prison and its prisoners, the world informs us of the unrest and injustice that’s currently occurring. The world, with all of its moments of silent loveliness, has its instances of sheer ugliness as well. For the sake of this exploration, it’s important to question and examine the very silent protagonists we’re sharing our experiences with. Are silent protagonists really silent?

Some may argue that the stripping away of a voice can equate to the removal of agency and power. However, the protagonists in Journey and Shadow of the Colossus are anything but silent. Though they speak a different language, they are constantly communicating with their voices. The musical tones erupting from the robed protagonist in Journey naturally aligns with the idea of music as a universal language. The protagonist doesn’t utter understandable words but it still tells its story through its consistent singing and chirping. When the protagonist’s singing gets weaker due to the mountain’s cold and unforgiving climate, it’s telling of us of its struggle to carry on. In the same vein, Wander from Shadow of the Colossus is in near constant communication with his horse. Whether he’s calling for his horse in the heat of battle or using a gentler tone when the animal is close by, there’s an incredible bond there. This horse serves as the link to the less isolating world Wander left behind.

The use of silence is fascinating in that can intensify a moment or create its own narrative. In positioning the world as a character again, the world can be either heroic or villainous or something in between. The transformative world in Journey speaks to a fairly complicated character or characterization. In thinking more about silent protagonists, I’m not sure if they’re really all that silent or represent the blank slate that players can project themselves onto. If a silent protagonist appears to be silent in the sense that they speak a different language or speak very little, take a moment to really listen to them. Sometimes silent protagonists are the loudest characters.

One thought on “Silence is Golden: A Closer Look at Journey and Shadow of the Colossus”

(copied from my Facebook response but to help proliferate dialog here)

In gaming, I usually equate silence, not with communication, but with mood and atmosphere (primarily survival horror).

One of my all time favourite moments in video game canon is in Chronotrigger, when Marle steps up into the teleporter. The Millennia Fair music in the sound track fades out – and there is this moment of silence, followed by the hum of the machine to start.

The entire sequence is executed very well, and gives you goose pimples to see it unfold.

I think of silence in Shadows of the Colossus, not when traversing the vast landscapes, but the moment after the hero has negotiated up the beasts and plunges his sword into the rune to deal damage – in this case the silence in broken and the music booms.

However, in terms of communication, I think of the older JRPG games, and not necessarily the silent progtagonist (such as Crono in Chronotrigger) – but the paradox created when a character has to say something, but the same time cannot. This is usually represented by the “….” or “dot dot dots”.

It’s a textual way to communicate silence – but it also conveys something. Dramatic pauses? Thinking? Words taken away because one is speechless?

The dot dot dot is kind of a silly trope, but at the same time, it’s multi-textual. However, I must bring up the subversion of the dot dot dot silence in the game Matt Hazard, where the titular character is about to fight a caricature of an anime boss who says “dot dot dot” causing Hazard to ask “what does that even mean?”

I really enjoyed reading this article.